An interview with the sole survivor of the Gowkadal Massacre.

January 21, 2022.

Present-day Gowkadal, Srinagar. Photo: Ahsaan Ali.

We spoke with Farooq Ahmed Wani, the sole survivor of the brutal Gowkadal Massacre in which 53 Kashmiris were fired upon and killed by India’s armed forces.

T/w: torture, graphic content, and violence.

On January 20, 1990, Indian army troops barged into several homes late at night in Srinagar’s Chota Bazaar neighborhood. During the raid, several were beaten, arrested, and there were many accounts of women being sexually molested as well. In retaliation, the entire locality marched and held protests against the incident. The locals planned a larger rally for the next morning, which would then turn into the Gowkadal Massacre that we know of today.

This massacre was the first mass killing in Kashmir of its kind and this day served as a catalyst to India’s systemic massacres and war crimes in the proceeding years.

*The interview is narrated word for word with minor edits to vocabulary and grammar.*

SWK: Where were you on January 21, 1990?

Farooq Wani: On this day, I was on duty for work where I worked as an engineer in the Public Health Engineering Department. There was a water shortage that day and I was told to collect a curfew pass from the Deputy Commissioner’s office in order to supply water to the affected areas. On my way to the DC office, I was stopped at Jahangir Chowk by Indian CRPF (Central Reserve Police Force) troopers. I showed them my ID card, but they were very dismissive and pushed me back. I decided to go through Amirah Kadal Bridge and reached Lal Chowk. At this point, I could hear faint slogans and the atmosphere seemed tense. It was around 10:45 am in Srinagar.

I decided to cross River Jhelum on a shikara boat and head back home. However, as I proceeded to go through Sheikh Baagh lane, more Indian army officers stopped me and didn’t allow me to cross. I panicked and felt trapped. Lastly, I decided to stay at my uncle’s house across Gowkadal Bridge until things calmed down.

SWK: How did you reach Gowkadal?

Farooq Wani: On my way to Gowkadal, the procession caught up to me and I joined the crowd. I could see Indian troopers surrounding the protestors with their fingers on their triggers. It seemed as if they were already advised to shoot at the protestors. I felt scared and knew something terrible was going to happen.

There were men and women in the procession. I walked closer to the ladies because I thought that the chances of getting hurt might be lower. We kept walking and chanting slogans such as “hum kya chahtay, azadi” (what do we want, freedom), “Islam zindabad” (long live Islam), and more. As soon as we stepped onto the bridge on Gowkadal, I heard one gunshot. Two seconds later, hundreds of bullets were being fired. They [Indian army] fired indiscriminately on those who were on the bridge. Everyone was screaming. The ladies were screaming and I realized that they were firing on the women as well. In front of me, I could see men falling to the ground.

In a fraction of a second, I decided to jump off the bridge and into the river. It was chaos and everybody was trying to jump in the water as well. As I ran to jump, a tall man pushed me to the ground and jumped into the Chuntkul (river) instead – I later learned that many of the people who jumped into the river to save themselves died because of the low water levels that month. I had fallen face down and I decided to lay down on the ground. After around 5 minutes, the indiscriminate firing finally stopped. As I lay down, I could see and hear people crying in pain. Some were shot in the chest, some in the legs, and some in the belly. The bridge was full of dead and injured people.

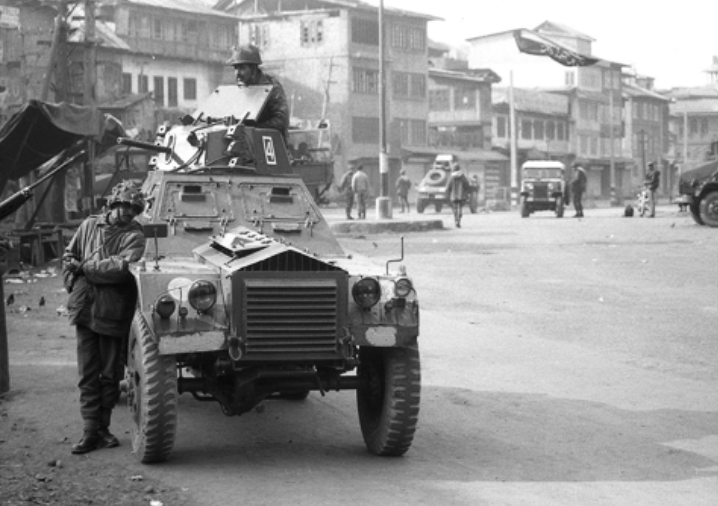

Indian soldiers standing guard one day after the Gowkadal Massacre. January 22, 1990. Photo: Mehraj Din.

Farooq Ahmed Wani, the sole survivor of the Gowkadal Massacre, at his residence in Kashmir.

SWK: How many bullets did the Indian army fire at you?

Farooq Wani: When I was laying on the ground, I luckily didn’t get shot at. I thought of standing up and running, but I could see an Indian soldier from the corner of my eye. He was holding a self-loading rifle (SLR) which holds deadly 6-inch bullets. I saw him aiming the rifle at the injured people and shooting them dead, one after the other. I was too afraid to get up so I stayed still.

I saw an Indian army platoon commander chasing more people down on the other side of the bridge. He then came towards my side of the bridge, along with 5 to 6 of his troopers, with a carbon gun in hand. They were aiming at the injured and shooting us down. The general and his troopers were aiming at the heads of the people. They were looking for any survivors and were gunning them down. They killed all the people on that bridge, nobody was left. This was deliberate. The injured could have been saved, but they killed them. They were picking up all the bullet shells and kept them in their pockets to hide evidence. I continued to presume to be dead. However, there was a Kangir (an indigenous Kashmiri portable wick heater carrying burning coal) next to my face and the ash which had fallen from the Kangir was burning the skin on my face. When it became intolerable, I turned my head to the other side. While I turned my head, an Indian soldier caught me moving and said “sir, ye zinda hai” (sir, he’s alive) to his army general. As soon as the officer came over to me, I got up halfway and on my knees and said “for God’s sake, don’t shoot, I am an [engineer] officer on duty”. The officer then said to me “Pakistan maangta hai? Islam maangta hai?” (Do you want Pakistan here? Do you want Islam here?) and fired at me several times until I fell to the side. I still remember the commander’s face vividly and the three stars on his uniform.

At this point, my face is up towards the sky. I realized that I was dying and I all I could think about were my two daughters and my third unborn child. I was on the ground wailing in pain when I saw another Indian soldier walk up to me. He put his gun on my temple and said “tu mara nahi abhi?” (you’re still not dead?). He was about to shoot me when the other officer who shot me earlier yelled out “goli mat zaya karo, mainay isko bohot goliyan maari hain” (don’t waste your bullets, I’ve already shot him several times). They were cursing me out in their Hindi language as well.

I felt my body burning and I was very thirsty. I could see a truck come by to pick up all the dead bodies. I saw a Sikh constable and I told him “bhaiya mujhay bhi uthao” (brother, pick up me too) and he put me in the truck, along with the other dead bodies. I was desperate to leave the scene because I knew that the army would not leave me if they still saw me alive. Thanks to the Sikh man and thanks to Allah, I was saved. When the truck stopped, I could hear a crowd of local Kashmiris ask the Indian soldiers driving the truck, “ismay kya hai?” (what’s in this?), to which the army answered “dead bodies”. As soon as the truck’s lid was lifted, I saw the crowd weeping and they yelled in Kashmiri “hey ye ha schu zinday!” (he’s still alive!). The truck had stopped at a police control room. The locals carried me out and took me to the doctor who was on duty at that control room. After the doctor assessed my vitals, I was then shifted to the hospital immediately.

SWK: Why do you think you survived?

Farooq Wani: This is cold-blooded murder. This is what you call genocide. 53 people were killed on that bridge. I could have been the 54th, but I am the lone survivor of this massacre. It was Allah’s will to keep me alive and stand witness to the massacre.

The commander who shot me had three stars and would have had about 30 soldiers working under him. I tried to trace him down to see who was in charge that day at that hour, but I was not able to find any answers. An FIR complaint (police report) was lodged for the massacre. The officer who was investigating the FIR was a Kashmiri Pandit and he reported that no evidence of human rights violations was found on site. Due to this, the case was closed. 53 people were murdered on that site and no evidence was found?

Our family has seen the worst face of the occupation. Nonetheless, I am thankful to God that I am alive to record this story. We will have freedom, InshAllah. Not my generation, maybe not yours, but we will be out of this suppression and occupation one day.

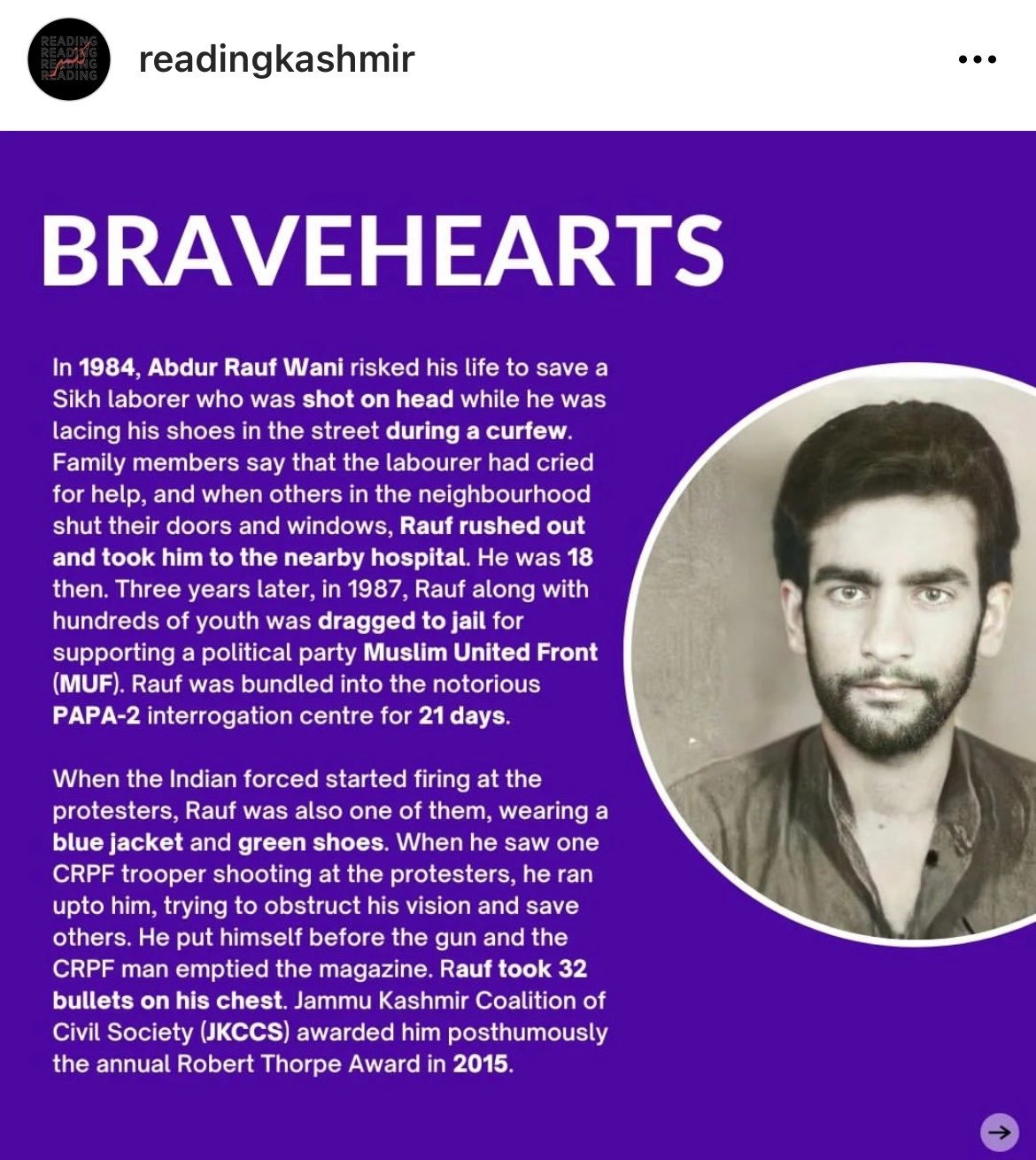

@ReadingKashmir from Instagram

SWK: When did you regain consciousness?

Farooq Wani: I regained consciousness in the recovery room at around 5:30 pm that day. At the end of my bed, I saw a young Kashmiri boy holding my shoes and weeping while looking at me. I called him closer to me and asked him if he could contact my family. I told the boy to inform them that I was slightly injured and would return back home tomorrow. I asked him to lie because I didn’t want my family to panic. However, the boy was weeping on the phone and told them that I had gotten shot and was laying in a bed at Srinagar’s State Hospital. My sister fainted as soon as she heard this. Luckily, my wife was nearby and handled the situation.

My wife and brother-in-law had to get curfew passes to see me – because Kashmir was put under a strict curfew right after the news of the massacre spread.

Ali Muhammed, an eye-witness to the massacre, recalls the incident that shook Kashmir. His teary eyes are enough to narrate the story that he witnessed on 21 January in 1990. “It was like doomsday. That terrible incident still haunts me. I can never forget the blood, caps, and shoes of the dead people scattered on the road…and how people running in different directions to save their lives”. Story: Urvat Il Wusqa, Photo: Ahsaan Ali.

SWK: How long did it take you to recover?

Farooq Wani: I was at the first hospital for 2 days. I was shifted to another hospital later where I spent 22 days. I went through two major operations and a few surgeries to remove all the bullets that were in my body. When I returned back home, I was bedridden for two months.

While I was in the hospital, I recall local and foreign journalists visiting me to hear my story. I was never scared to tell them what I eyewitnessed.

SWK: Do you believe justice will be served for what happened that day?

Farooq Wani: No one from the Indian state came forward with a detailed investigation into what happened that day. The only individual that reached out to me was the advisor to Governor Jagmohan, Hameedullah Khan. He told me that he’d like to award me for my bravery, but I refused it. I told him that the best award would be to catch hold of the culprits who killed all those people in that ruthless manner. He [the Indian army commander stationed at the massacre site] should be tried in court for killing 53 Kashmiris, along with Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) Allah Baksh who ordered the Indian army to open fire at the protestors. After the Gowkadal massacre in 1990, Kashmir became numb to such systematic massacres. Even today, people are afraid to come out of their homes.

32 years that passed and he [the Indian army commander in charge that day] has never been questioned or called by any commission. He is always infront of my eyes. I tell you, 32 years have passed and I can still recognize him. I remember how he was pumping bullets in people. [I remember] I told him that I am an officer on duty and said “for God’s sake, don’t shoot” and he still shot me. This is cold-blooded murder. Everything is in the hands of Allah, I am not afraid of telling the truth.

Farooq Wani, the sole survivor of Gowkadal Massacre, speaking at the anniversary of the massacre in 2018. Source: Kashmir Newswire.

SWK: Can you describe how you cope with your trauma?

Farooq Wani: The aftermath of such traumatic war crimes is very important to note. Initially, I lost a lot of blood and turned very timid emotionally. Whenever I would see an Indian soldier, I was triggered and would get very scared. I also could feel my brain getting tired very often. I used to see a psychiatrist and was under neurological treatment for a very long time. I used to feel as though I wouldn’t be able to survive much longer. With time, I slowly came back to “normal” life.

The trauma is still there. I am angry. I will always be angry about what happened. I cannot forget how brutally they [India] killed our people. I saw the ugly faces of the Indian armed forces. They are inhuman. After the massacre, I witnessed several crackdowns in my neighborhood. They [Indian army] would come and break our doors. If you look at my rooftop, you’ll see several bullet holes. The Indian army fires at our homes just for the heck of it. They would burn the houses [within the neighborhood]. My elder brother, Dr. Professor Abdul Ahad Wani, was killed by the Indian intel agencies. My brother-in-law was picked up by the Indian army from his showroom in Lal Chowk during a crackdown and was thrown in jail. He was tortured in an interrogation center for six months without reason. When he was released, he only survived a few more months before passing away. He told me that he wouldn’t survive much longer because he used to get beaten ruthlessly on his head with iron rods. He had developed serious neurological problems due to the torture the Indian state put him through.

SWK: What would you like to tell the current and future generations of Kashmiris?

Farooq Wani: I have spilled my blood and more than 100,000 Kashmiris have been killed by the Indian state. India is not backing down. We have to sustain our movement. They want to change our demography and want us to leave Kashmir. They will make colonial settlements like Israel.

If we surrender, we will vanish. Their intentions are clear. For the sake of the people and children that have been killed, please resist India’s occupation and contribute your bit. We need to save Kashmir and Kashmiris.

![“By hanging their heads, spilling their blood on the ground in way of truth; by saving the country’s garden, you raised the dignity of Muslims,” reads the memorial erected by Khan. “[This stone is] a tribute to 21 January 1990 in Gaw Kadal, Basant Bagh martyrs who gave their lives for their beloved country.” To crystallize the memory of the first militancy-era massacre, a youth erected a memorial stone at Basant Bagh. Years later, after he himself became a conflict casualty, a memorial stone was erected for him on the same spot. (via FreePress Kashmir). Photo: Ahsaan Ali.](https://standwithkashmir.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IMG_4782-01-scaled.jpeg)

“By hanging their heads, spilling their blood on the ground in way of truth; by saving the country’s garden, you raised the dignity of Muslims,” reads the memorial pitched by a Kashmiri youth by the name of Showkat Ahmad Khan. “[This stone is] a tribute to 21 January 1990 in Gaw Kadal, Basant Bagh martyrs who gave their lives for their beloved country.” To crystallize the memory of the first militancy-era massacre, Khan (also known as Nana) erected a memorial stone at Basant Bagh. Years later, after he himself became a conflict casualty, a memorial stone was erected for him on the same spot. (via FreePress Kashmir). Photo: Ahsaan Ali.

Stay in touch with Stand with Kashmir.

Stay updated with Kashmir’s history and the dates Kashmiris commemorate, such as the Gowkadal Massacre’s yearly anniversary, by ordering our 2022 Calendar! This calendar includes twelve illustrations by indigenous artists from occupied Kashmir. Each illustration delves into ways the Indian state has implanted its machinery to systematically disfranchise, disempower and criminalize Kashmiris while strengthening its colonial hold in Kashmir. In this calendar, we are attempting to put a spotlight on some key events that have shaped the history of Kashmir and draw attention to a fraction of the war crimes committed by India.

Stand With Kashmir (SWK) is a Kashmiri-driven independent, transnational, grassroots movement committed to standing in solidarity with the people of Indian occupied Kashmir in ending the Indian occupation of their homeland and supporting the right to self-determination of the pre-partition state of Jammu and Kashmir. We want to hear from you. If you have general inquiries, suggestions, or concerns, please email us at info@standwithkashmir.org.

©2025 StandWithKashmir All rights reserved. SWK is a 501(c)(3) non-for-profit organization.

Leave a Reply