September 18, 2025

Songs of Paradise opens with a woman singing. By the time it ends, Kashmir has disappeared entirely. This is not an accident. This is the point.

The film claims to tell the story of Raj Begum, Kashmir’s first female radio singer. What it actually does is replace her entire life with something more palatable. Start with her husband. The real Raj Begum married Qadir Ganderbali, Deputy Inspector General of Police under Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad. Kashmiris called him “Ister” (Iron Press) because that was his interrogation technique. Hot iron on skin. The film decided this was too complicated, so they invented a poet named Azaad Maqbool Shah. In their version, he is the progressive one talking about ‘inqilaab’ (Revolution) through her voice, pushing her to take opportunities, while she worries that her singing, if exposed, will bring ‘toofan’ (Storm). They literally reversed the power dynamic. They made the woman afraid of her own voice and the man her liberator. When a photo of them together causes scandal, he nobly marries her to protect her reputation so she can keep singing. Without him, her career ends. With him, she becomes a feminist icon. This is the “feminism” the film sells: a woman who needs male permission to exist in public.

Saba Azad plays young Raj Begum with an accent that sounds like mockery. Her Kashmiri is phonetically learned and that is understandable, she doesn’t speak it. But why make her speak it at all? Worse, even her Urdu comes out in this exaggerated ‘Kashmiri accent’ Bollywood uses in comedy shows to mock us, the same accent Indian influencers put on when they joke about Kashmiri shawl walas selling shawls in India. The older version, played by Soni Razdan, speaks normal Urdu. No accent. Nobody explains why young Raj Begum sounds like a parody while old Raj Begum sounds like she is from Mumbai. Nobody asks. The film barely has any actual Kashmiri dialogue anyway. Everyone speaks Hindi or Urdu, even the actors who actually know Kashmiri. At one point, the mother-in-law character looks at the fictional poet husband and calls him ‘my handsome zaamtur’ (son-in-law). The audience is meant to find this cute, charming, and the traditional woman accepting the modern match. But listen to what is actually happening: the London-returned man is positioned as the family’s savior, the women exist to be grateful for his presence, and this is presented as progress.

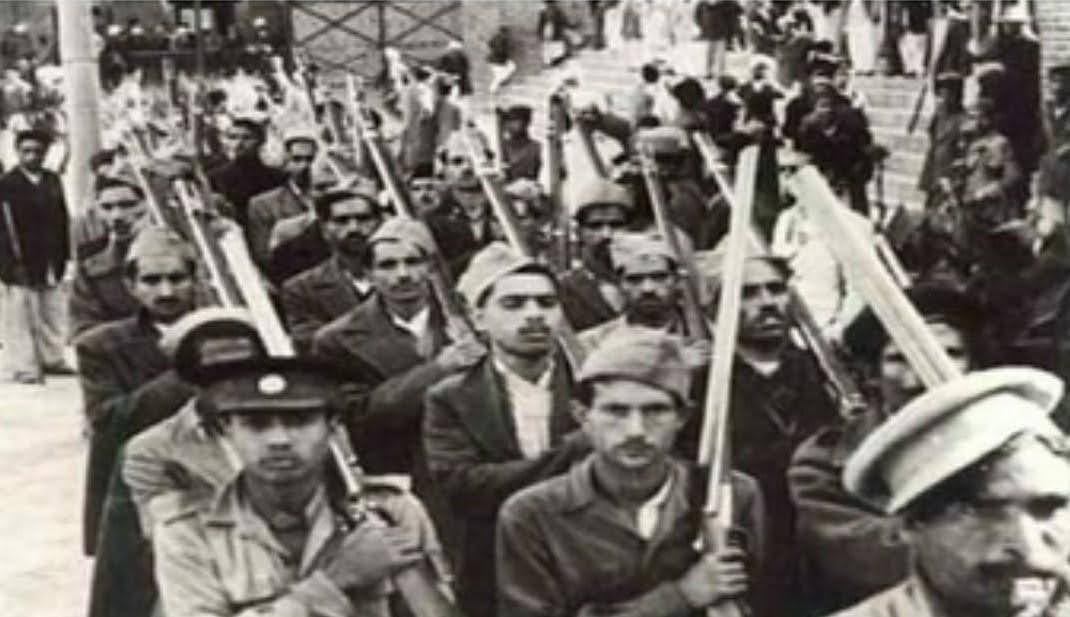

The real Ganderbali ran the Khoftan Fakirs during the 1950s and 60s. These were a state-sanctioned vigilante group who got their name because they operated after Isha prayers. Khoftan means night prayers in Kashmiri. After those prayers, they would march with wooden sticks and axes, breaking into homes of anyone suspected of wanting a plebiscite. Radio Kashmir, where Raj Begum sang, was created by the same administration that gave Ganderbali his power. The station was built in 1947 as a tool for ‘psychological integration’ and to teach Kashmiris to stop being Kashmiri and start being Indian. Every morning started with the Indian national anthem. Every song Raj Begum sang had to be approved by the same people who approved the interrogations.

The film shows none of this because it cannot show this and still tell the story it wants to tell, which is a story about art existing beyond politics, about individual triumph over collective oppression, about feminism that threatens nothing except local patriarchy. So Radio Kashmir becomes just a building where music happens. The husband becomes just a supportive partner. The struggle becomes just about conservative society versus modern women. Kashmir becomes anywhere.

This is how Bollywood has always consumed Kashmir. Either as a paradise for honeymoon songs, Switzerland when Switzerland was too expensive, or as a battlefield for nationalist drama where brave Indian soldiers fight Pakistani terrorists. Both versions erased actual Kashmiris. We existed as backdrop, never as people.

Now they have found something more sophisticated than using our landscape. They get Kashmiris themselves to tell sanitized stories. The film is made by a Kashmiri, which provides perfect cover. His identity becomes their authenticity. When we criticize the film for erasing Ganderbali, for inventing a poet, for removing the occupation, they can say: but a Kashmiri made it. This is more dangerous than when outsiders mistell our stories, because it cannot be dismissed as ignorance. A Kashmiri chose to erase the torture. A Kashmiri chose to invent the romance. A Kashmiri chose to make our occupation disappear. What the film is really doing is teaching Indians that Kashmir’s problems are cultural, not political. That what Kashmiri women need is not liberation from occupation but from tradition. That our stories make sense without the context of violence that shapes them. They give us problems that can be solved without mentioning that Kashmir is occupied.

The diaspora Kashmiris celebrating this film show something important about how distance works on memory. They need to believe that Kashmir can be understood without understanding occupation, that our culture can be preserved while our politics are erased, and that they can be both Kashmiri and Indian without that being a fundamental contradiction. The film gives them what they need: Kashmir as culture without Kashmir as conflict, identity without resistance, songs without the machinery that broadcasts them. Watch them share it from California to London with captions about ‘our stories finally being told,’ never asking whose version of our story this is.

Songs of Paradise ends where it began with the Indian student who came to Kashmir for his thesis. He found his life’s purpose in Raj Begum’s story, he tells us. Her story became his purpose. He stands on stage talking about destiny and how no one tried to preserve her creations. Nobody tried to preserve them. As if we destroyed our own archives. As if occupation doesn’t determine what survives and what burns. He introduces her granddaughter to sing for his project, what he calls their ‘small effort.’ The film closes with Indian state honors listed on screen. Padma Shri. Melody Queen of Kashmir. The audience leaves feeling they have witnessed something brave and authentic. They have actually witnessed their own comfort being prioritized over our truth. They have watched Kashmir disappear into paradise, Ganderbali disappear into a poet, occupation disappear into culture, and Raj Begum herself disappear into an Indian student’s journey of self-discovery. They have watched us disappear into versions of ourselves that make them feel better about what is being done to us.

This is how we vanish: not in silence but in misrepresentation, not all at once but story by story, not against our will but with our participation. We vanish into the stories they need us to tell, the songs they need us to sing, the paradise they need to believe exists. The saddest part is not that they tell these lies but that we have started to believe them. That some Kashmiris watch this film and feel seen rather than erased. That we have been so gaslit about our own reality that we mistake ventriloquism for voice. That we celebrate any representation without asking what is being represented and what is being replaced. Songs of Paradise is not about Kashmir. It is about what India needs Kashmir to be. The difference matters, even if we are the only ones who can see it.

Stay in touch with Stand with Kashmir.

Stand With Kashmir (SWK) is a Kashmiri-driven independent, transnational, grassroots movement committed to standing in solidarity with the people of indian-occupied Kashmir in ending the indian occupation of their homeland and supporting the right to self-determination of the pre-partition state of Jammu and Kashmir. We want to hear from you. If you have general inquiries, suggestions, or concerns, please email us at info@standwithkashmir.org.

Leave a Reply